Philip Whalen; Beset by Irony

If Philip Whalen is crowded by beauty as the title of David Schneider’s biography, Crowded By Beauty, The Life And Zen of Poet Philip Whalen (University of California Press, 2015) suggests, he is also beset by irony. Crowded By Beauty traces the life arc of the most remarkable American poet of the latter half of the 20th century. The irony is that he is practically unknown in the world of American letters.

As Schneider, himself a Zen priest and archaya in the Shambala lineage, points out in his introduction, “Whatever Philip Whalen’s accomplishments, when it came out in ordinary conversation that I was writing his biography, the response was very often a blank look and an uncomfortable silence. To furnish identification I might say “poet,” then “Zen master,” and finally “one of the Beat poets.” This inevitably led to a list of three of the most famous: Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder. For those who don’t know Philip Whalen, it seemed initially necessary to name these names, though they constitute a very incomplete list both of Beat poets and of Whalen’s friends.”

In some ways, Philip Whalen was an anachronism, a throwback to an era when writing was done with a pen and music was made in a parlor. Though seemingly out of his time, he was very much of his time when he came into his own in the latter half of the 20th Century, tuned in to jazz and modern art, sharpening his contemplative skills on the whetstone of poetry. He may have come across as an old fashioned guy who admired Samuel Johnson as much as the ancient Chinese masters, a real fuddy-duddy by all accounts, an old school autodidact (think Kenneth Rexroth) yet his was a radically modern turn of mind as reflected in his approach to poetry.

“A continuous fabric (nerve movie?) exactly as wide as these lines” is how Whalen explains what he was attempting with his poetry, “continuous” within a certain time-limit, say a few hours of total attention and pleasure: to move smoothly past the reader’s eyes, across his brain: the moving sheet has shaped holes in it which trip the synapse finger-levers of reader’s brain causing great sections of his nervous system—distant galaxies hitherto unsuspected (now added into International Galactic Catalog)—to LIGHT UP. Bring out new masses, maps old happy memory.” Elsewhere, Whalen likens his poetry to “a picture or a graph of a mind moving, which is a world body being here and now which is history. . . and you.” Reading Whalen’s poetry is to partake of a continuous stream of consciousness monologue/dialogue dream nerve movie echoing Heraclitus in that the poem, as framed sentience, is a shape shifting undulation which one can step in and out of in the process of being.

Schneider’s approach to his biography of Philip Whalen, a Zen pioneer in the West who was also an extraordinary American poet, is to present a base of testimonials from the afore-mentioned literary figures of Ginsberg, Kerouac, and Snyder as well as from Lew Welch, Joanne Kyger, and Michael McClure among other literary sources. Gleaned from letters, interviews and anecdotal material, Whalen’s accomplishments as an important American poet is described through his close relationship with his contemporaries to assure that he is not dismissed as merely some ancillary fixture to the Beat phenomenon. The literary material is followed by the biographical tracing of Whalen’s eventual commitment to Buddhism. Whalen’s literary aspect looms larger because it is richer in documentation (notebooks, letters, interviews, lectures) as well as a body of work, The Collected Poems Of Philip Whalen (Wesleyan, 2007).

In the early chapters of Crowded By Beauty Whalen’s friendship with Jack Kerouac is shown to be of a genuine sort. Theirs was a fraternal camaraderie in which Whalen served as the older brother who also functioned as a kindly mentor and adult sensibility. In their correspondence, Kerouac and Whalen make clear the respect and brotherly esteem they had for each other. And that Allen Ginsberg’s friendship with Whalen elicited a lifelong proprietary concern and mutual respect as well as a free ride on the ‘G Train’ even though Ginsberg is quoted as saying he didn’t really “get” Whalen’s poetry. Over the long years of their friendship, Allen Ginsberg looked after Philip Whalen’s interests, including him in land deals in the Sierra foothills and regularly inviting him to lecture during the heady early days of the Naropa University Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics. As well the relationship with Gary Snyder and Lew Welch, Whalen’s Reed College cohorts in Portland, is given close attention. It was Gary Snyder who often provided his older friend with shelter from the storms of unemployment and uncertainty. And it was due to Snyder’s efforts that Whalen found employment in Japan teaching English which afforded the poet his greatest peace of mind and creative stability. Lew Welch and Whalen were running buddies, an honest affection formed while they were undergrads at Reed, searchers, similar to maverick young intellectuals everywhere, unaffiliated yet with a certain sense of personal destiny. They both loved Stein and Williams, Dickinson, too, and based their aesthetic on the irregularities of spoken language.

The surprising portrait in this biography is that of Michael McClure, depicted as Whalen’s Frisco chum, a family guy with wife and kid, someone with the common sense and empathy to check in on an indigent poet at loose ends, to let him sleep on the couch, and feed him when he was hungry. Phil Whalen and Mike McClure were the odd couple, the handsome young poet and the older pear-shaped walking encyclopedia. McClure’s iconoclasm served as a counterbalance to Whalen’s scholarly reserve. Joanne Kyger, an exceptionally talented young poet in the Bay Area literary scene of the late fifties, was introduced to Whalen in the early days of her relationship with Gary Snyder, a fortuitous meeting that led to a lifetime of friendship and devoted affection. Of all the poets, Joanne Kyger’s and Philip Whalen’s poetry reflect similar concerns and approaches to the making of their art.

The picture of Whalen that emerges from the biography is of an intellect preoccupied with the practice of poetry. Much as the mendicant monks of old, he believed that because he was a poet the world would provide as it always did for holy men. If there were a soundtrack for this section, it would be Joe Cocker singing With A Little Help From My Friends. This is not to suggest that all is sweetness and light in the literary milieu. Jack Spicer despised Whalen’s poetry and once offered to pay Whalen not to read his poems in public. Robert Duncan resented the Northwestern backwoodsmen’s intrusion into his domain, especially after one of them ran off with the princess. Charles Olson found Whalen an exasperation, and called him “a great big vegetable.” Even today Whalen is often conveniently overlooked in anthologies representative of American poetry.

Crowded By Beauty gathers a narrative out of the literary specific biographical material that clearly illustrates the importance of Whalen as a significant poet in the American canon. Primary among that designation are three American poets who have opened the door to the adjacent possible for a unique native prosody. Walt Whitman turned ancient praise songs briefly glimpsed in the Bhagavad Gita on himself as a view into the luminous self. William Carlos Williams abolished the past (goodbye ubi sunt) with the immediacy of the moment in the lightening flash of perception. Philip Whalen graphs the remembered present as pictures of the mind moving against a field of attentiveness and cerebration.

To appreciate Whalen and his poetry one must first understand his place in relation to the rest of AmLit and the maverick lineage of Whitman, Dickinson, Stein, and Carlos Williams. His is an intrinsic understanding of musing and amusement, of how a savvy sense of music composition (Bach, Schopenhauer, Jazz ) combined with an intuitive comprehension of the modern can be recorded as the lyricism of being in the world attentively. There is never any doubt that his poems are shaped by an artist.

An interesting point of literary taxonomy is briefly raised in that, with the exception of Kerouac and Ginsberg, most of the poets of Whalen’s orbit are mislabeled. They are lumped in with the Beat writers largely through their association with Ginsberg and Kerouac, the historic Six Gallery’s reading, in which Whalen and Snyder participated, and the recreation of that event in Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums. These poets, along with Welch, McClure, Kyger among many others of that and subsequent generations, are in fact better served by being viewed as Pacific Rim writers. The Pacific, as Rexroth pointed out, like the steppes, joins as well as separates. There is natural empathy, a curiosity for cross water Eastern cultures. The sensibilities of the East inform these writers and it should be of no surprise when they embrace aspects of that enculturation as the result of the post-war occupation of Japan. Whalen and Snyder work the most complete synthesis by rigorously following the path to Buddhism.

In contrast to Gary Snyder’s stature as a major contributor to American poetry, his old college pal, Philip Whalen, suffers the ignominy of being known as a poet’s poet, too good (and too difficult) for the hoi-polloi which serves to damn him with those who think poetry is too obscure to begin with. Yet Whalen’s poetry is the most brilliant expression of personal awareness ever set down (appreciated) by the modern mind. In the vast field of the epic length poem Scenes From Life At The Capital written while living in Kyoto, the picture of a mind moving comes together as a full length neural feature. Although the breadth of Whalen’s poetry is consistently brilliant from the beginning, it is in work from his time in Japan that his poetry reaches the apex of excellence.

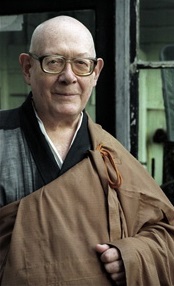

Whalen’s entry into the dharma life is a different story and as such begins with his birth. Whalen was born in 1923 and raised in eastern Oregon, a creative young man with a penchant for drama and music. He was bookish in the parlance of those days. Drafted into the Army Air Corps toward the end of the Second World War, he later attended Reed College in Portland, most likely on the GI Bill. San Francisco acted like a big culture magnet on Whalen and his cohorts, Welch and Snyder, and drew them to a sense of place amenable to their pan-Pacific sensibilities. Gary Snyder’s commitment to Zen was mirrored, though less rigorously, in Whalen’s intermittent attempts and profound intellectual struggle with what Zen entailed, a negation of that illusory mental property. Whalen’s sojourn in Japan as a teacher of English reinforced certain conclusions and intuitions about the practice of Buddhism. Subsequently Baker Roshi offered Whalen sanctuary at the San Francisco Zen Center. The poet, then in his fiftieth year with no likely prospects of employment, accepted the succor. For the next thirty years Philip Whalen, who finally accepted the transmission and became known as Zenshin, lived his life as a Buddhist monk of the Soto Zen lineage, primarily in San Francisco, ending his days as the abbot at the Hartford Street Zen Center. He achieved personal entropy in June of 2002.

As a contemplative, Whalen finally found a job that he liked, one that suited him. The self comfort of contemplation was an increment above the relentless cerebration of self consciousness. He no longer had anything to complain about (not that he ever stopped complaining) and so the poems stopped. The complaints were taken care of in the practice of meditation. As he said in an interview (Beneath a Single Moon, 1991), “A far as meditation is concerned I’m a professional. I’ve been a professional since 1973. And that’s my job. Maybe that’s where poetry comes into all this, that it has to be an articulation of my practice and an encouragement to you to enter into Buddhist practice.” And you have to take him at his word.

If there is a lesson in the life and Zen of poet Philip Whalen, it is about comportment and humility, about the value of being a poet, of practice over product and self-aggrandizement. Here modern Western Buddhism is served on the plate (or bowl) of what Donald Allen termed “the new American poetry” as exemplified by Philip Whalen. In his later life, the dharma path subsumes the egocentricity of the poet in allowing him a way out of the world of red dust.

Commenting on the Collected Poems of Frank O’Hara when it was first published in 1971, Whalen compared the tome to a tombstone. Perhaps the 550 plus pages seemed a trifle excessive at the time, yet Whalen’s own posthumous collection of poems weighs in at a hefty 900 pages. In an elegiac vein Crowded By Beauty might be viewed as an eulogy, touching on the associations, the milieu, and the context of Whalen’s scholarship and writing. It serves as a reminder that among all the celebrity and cachet of rebelliously prescient intellects, the one most radical in his approach to American poetry has been overlooked. With Crowded By Beauty providing a time line and anecdotal reference on the one hand, and the chronological arrangement of the poems in the Collected Poems Of Philip Whalen supplying the corpus on the other, perhaps now the real work of appreciation and acknowledgement can begin.

(This piece first appeared on The New Black Bart Poetry Society website. Our thanks for giving permission to reprint.)

Pat Nolan lives along the Russian River in Northern California. His poems, prose, and translations have appeared in literary magazines and anthologies including Rolling Stone, The Paris Review, Big Bridge, Otoliths, Fell Swoop, Triada, Saints Of Hysteria, Poems For The Millennium, Vol. I, and Up Late, American Poets since 1970. He is the author of numerous collections of poetry, most recently, Your Name Here (Nualláin House, 2014). He has published two novels. His online serial novel, Ode To Sunset, A Year In The Life of American Genius, is currently posting installments at odetosunset.com

Nolan is also publisher at Nualláin House, Publishers (nuallainhousepublishers.com) and maintains Parole, blog of the New Black Bart Poetry Society. In the fall of 2015 Nualláin House issued Poetry For Sale, a collection of haikai no renga (linked poetry) written over a period of 30 years by Keith Kumasen Abbott, Sandy Berrigan, Joen Eshima, Gloria Frym, Steven Lavoie, Pat Nolan, Michael Sowl, and John Veglia.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home